What is Akira? A Cultural Supernova

Calling Akira a mere ‘film’ is like calling a supernova a ‘bright light’. This project was a cultural explosion, fusing cyberpunk grit with existential dread and animating it with brutal precision. Decades later, its influence casts a long shadow over anime and popular culture.

Watching this for the first time properly unsettled me; I did not just feel entertained. Neo-Tokyo, with its neon-soaked decay and rampant corruption, felt like a warped mirror reflecting the modern world. Every frame whispered a potent warning: this could well become our future.

I absolutely adore this feature.

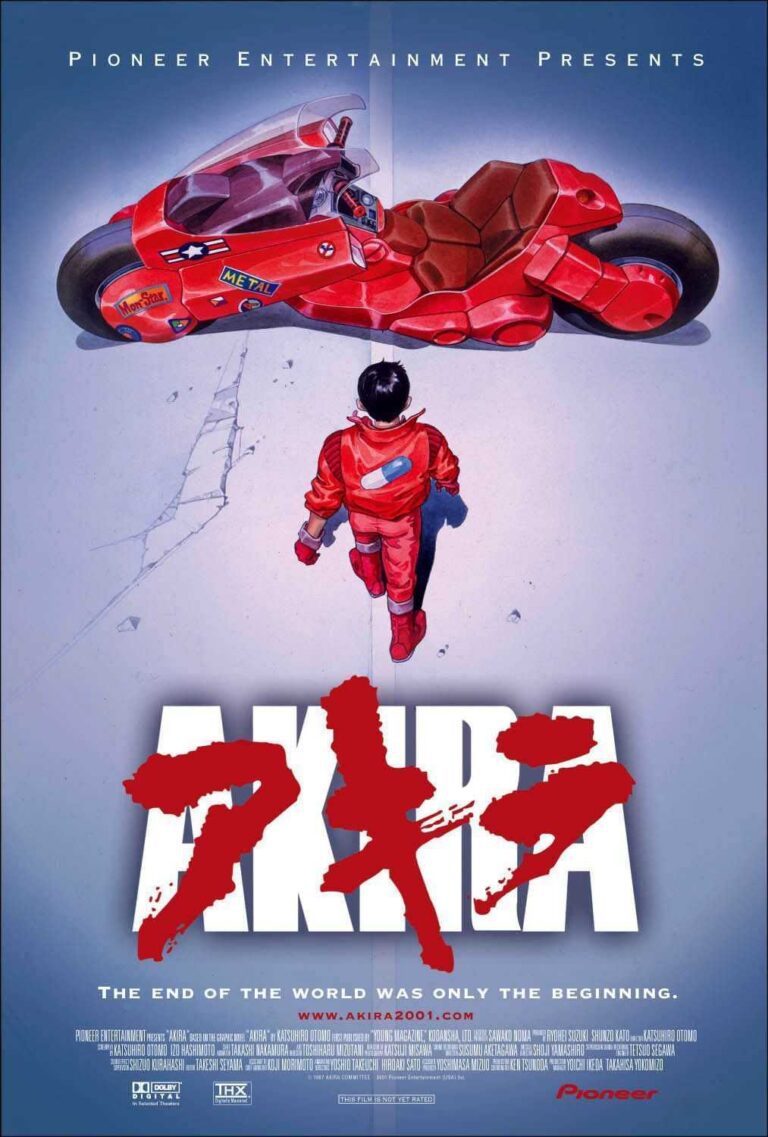

Katsuhiro Otomo, directing and adapting his own sprawling manga, released Akira in 1988. The production did not just push animation boundaries; it obliterated them. At the time, the $5 million budget seemed unthinkable for an animated work. Despite this, every yen scorches the screen. From Kaneda’s iconic motorbike slide to Tetsuo’s grotesque transformation, this was pure alchemy, not simply animation.

Akira: An Overview

Spoilers ahead!!!

During the 1980s, anime remained a niche curiosity outside Japan. Then Akira crashed into global cinemas like Kaneda’s bike smashing through a riot. It exploded. The giant budget translated directly onto the screen, pouring out in a frenzy of hand-drawn agony and ecstasy.

Over 160,000 animation cels brought Akira to life; the work genuinely lived and breathed. Hyper-detailed brilliance sprawled across the cityscapes; each frame vibrated with a unique style. Few had ever witnessed anything comparable. Even today, the sheer craftsmanship turns heads and drops jaws.

Crucially, the film delivers substance, not just style. Japan’s post-war anxieties, its fear of power spinning out of control, and a deep-rooted mistrust of institutions surge through the film’s veins. These themes are the beating heart of Akira. They lend the chaos meaning, ensuring the spectacle lingers long after the credits roll.

Then comes the ending: a swirling, psychedelic nightmare. It grabs you by the throat and utterly refuses to let go. Bewildering, beautiful, and terrifying, the conclusion leaves you gasping for air, wondering exactly what you have just witnessed.

In short: this film changed everything for me.

The Plot: Chaos Drives the Story

Neo-Tokyo, 2019. The city hums like a live wire, ready to snap. Militarised police flood the streets, anti-government protests rage, and biker gangs tear through the ruins of an older Tokyo, obliterated long ago by an enigmatic force known only as Akira. This world simmers with unrest, making hope feel like a bad joke.

Kaneda and Tetsuo stand at the centre of this chaos. Childhood friends, history binds them, but destiny rips them apart. Their story focuses on the brutal cost of power and how quickly it corrupts. As the city crumbles around them, their bond fractures, leaving only wreckage behind.

Without revealing too much: Tetsuo’s psychic abilities awaken, bringing catastrophic consequences. His transformation proves horrifying yet impossible to look away from, becoming the film’s relentless, terrifying heartbeat.

Meanwhile, the government’s secret experiments simmer beneath the surface, brewing their own disasters. Cult-like reverence surrounds Akira; this worship grows feverish, almost infectious, as the city spirals further into madness. Kaneda, caught between loyalty and survival, barrels into the chaos with a recklessness only youth affords.

The threads snap during the third act. What follows is not a tidy climax but a cosmic scream, a collapse of reason and reality itself.

Character Dive: Two Sides of a Coin

Kaneda: The Rebel Who Grew Up

Kaneda bursts onto the scene like a firecracker. His red bike gleams, a cocky grin plasters his face, and he shows complete disregard for authority. He is the sort of chap you would half admire, half want to punch. Yet, Kaneda’s bravado hits a wall when Tetsuo’s terrifying transformation begins. His fierce loyalty clashes hard against a desperate instinct to survive.

Kaneda’s journey avoids traditional heroism. He does not save the day with grand speeches or noble ideals. Instead, he learns a bitter truth: no one commands this chaos. He stands firm in the end, knowing the storm might crush him.

That final act proves raw, cruel, and heartbreakingly human.

Tetsuo: A Tragedy Written in Blood

Kaneda is the fire—wild, relentless. Tetsuo is the spark setting the entire world ablaze. His fall represents a story of identity crumbling under unbearable pressure. With every grotesque mutation, something precious slips away: first his friendship, then his humanity.

Watching Tetsuo unravel registers as both horrifying and tragic. His desperate hunger to be seen, to matter in a world that always dismissed him, ultimately dooms him. By the end, he becomes a wounded child, screaming into an endless void.

Their bond—Kaneda’s reckless loyalty and Tetsuo’s fragile pride—forms the story’s soul. When this bond finally snaps, the world breaks and your heart breaks too.

Key Themes Explored:

Akira’s Bleeding-Edge Warnings

Akira forces you to breathe the dystopia. The city’s filth, corruption, and chaos seep into every frame, clawing at the same anxieties plaguing us today. Government corruption stands not as a background detail but as a reflection of real-world systems. Those in power tinker with human lives as disposable experiments. The film’s depiction of technological advancement avoids wide-eyed futurism; it shows disaster unfolding.

The true core of Akira exists in its explosions, but also, in the small, gutting tragedies rippling underneath. Strip away the chaos, and the remaining material feels painfully human: friendship poisoned by envy, loyalty cracked by ambition, and innocence twisted into something monstrous. Kaneda and Tetsuo’s bond shatters, and each fragment cuts deeper as the story spirals toward its nightmarish conclusion.

Tetsuo’s descent haunts the viewer. His newfound power does not liberate him—it isolates him too. Every destructive act feels like a desperate scream for recognition in a world that either exploits him or fears him. Ultimately, the film examines the agony of being unseen, unheard, and finally, undone.

Growing Up with a Dark Twist

Most coming-of-age tales conclude with bittersweet wisdom. Characters understand themselves and the world better. Akira, however, offers no such mercy. It closes with a universe tearing itself apart, screaming in anguish. Tetsuo’s metamorphosis—his body mutating, his mind fraying—strips adolescence of sentimentality. It amplifies growing up into full-blown body horror. Every teenager feels betrayed by their changing body at some point, yet Akira transforms that metaphor into a raw physical reality. Limbs stretch into alien forms; veins pulse with monstrous energy Tetsuo cannot master. This depicts puberty as a cosmic punishment.

Meanwhile, Kaneda’s path to adulthood unfolds differently. His transformation proves no less devastating. Starting as a cocky youth, swaggering through the city with a gleaming bike and a sharp grin, Kaneda believes rebellion makes him mature. Reality dismantles that illusion piece by piece. By the end, he has ceased being a boy chasing thrills—he is a battle-worn survivor, staring into the vast, indifferent darkness of Neo-Tokyo. Growing up here means realising your insignificance against forces that do not care if you are ready. Kaneda must take tough decisions.

Power, Corruption, and the Monsters We Create

Power functions not as a blessing but as a cancer spreading uncontrollably. Tetsuo, desperate to claw his way out of a lifetime spent in Kaneda’s shadow, seizes strength. He believes it might save him. Yet the tighter he grasps, the faster he slips into madness. The government’s psychic experiments mirror this tragedy: they turn children into weapons, only to recoil in terror when those weapons refuse to obey.

Even the so-called revolutionaries, waving banners of freedom, reveal their own hunger for control. They hold their rifles tighter than their ideals. Through every collapsing building, Akira hammers home a crucial truth: power magnifies what lies beneath, and this often translates into pure, festering fear, not heroism.

The Visual Brilliance of Akira: A World That Breathes (and Bleeds)

Neo-Tokyo as a Living Nightmare

You breathe the foul air and feel the cracked pavement under your feet. The oppressive weight of Neo-Tokyo’s skyline bears down in every opportunity.

Riots crackle like a living fever across the city’s veins. Each scene feels so tactile you might swear you smell the burning tyres and electric neon. Today’s computer-generated imagery boasts realism, but Akira’s painstakingly hand-drawn animation—over 160,000 individual cels—makes most modern productions appear hollow.

The City as a Reflection of Collapse

Neo-Tokyo stands as the true antagonist, a bloated corpse of civilisation kept twitching by greed, violence, and broken promises. Its skyscrapers, vast and brutalist, loom like tombstones over the poverty festering below. Streets glow with sickly neon, while signs sputter like dying stars. Akira’s city offers no beauty in decay—only the sick certainty that collapse is inevitable.

Take the infamous bike chase. Beyond its action, it serves as a frantic tour through the chaos: crumbling infrastructure, screaming citizens, flashing sirens. Here, lawlessness represents the system, not a glitch within it. Neo-Tokyo lives, but only because it refuses to die properly.

Societal Commentary Through Environment

Otomo stitches society’s collapse right into the bones of Neo-Tokyo. The Olympic Stadium, meant to symbolise hope and rebirth, stands like a sad joke, a hollow monument to a future that never arrived. The Ruins of Old Tokyo lurk underfoot like a stubborn memory. Every broken streetlight reminds you that this city’s foundation comprises rot pretending to be progress.

And the crowds? They are not just angry extras. Each protester looks like someone teetering on the edge—beaten down by broken systems, finally snapping. One moment they march with signs; the next, they loot. Otomo paints them not as villains or heroes but as people caught in a machine that chews them up regardless.

Neo-Tokyo feels like a potent warning. It holds a mirror up to post-war Japan, a country sprinting into the future so fast it left half its soul behind. Rapid modernisation birthed skyscrapers and bullet trains, certainly—but it also bred isolation, alienation, and a gnawing sense that none of it fixed anything.

Does this sound familiar? Walk through any packed city today, and you see the same tired faces, the same concrete jungles, the same quiet, seething rage bubbling just under the surface.

Akira's Cultural Footprint

Western impact

When people discuss the anime boom in the West, they mean Akira. Before its release, anime remained a niche curiosity outside Japan, often dismissed. Akira hit like a thunderclap. Suddenly, the West realised animation could be brutal, beautiful, and aimed squarely at adults.

Akira’s success opened the floodgates. Without it, we might never have seen Ghost in the Shell stretching minds or Princess Mononoke finding new audiences. Even stylish classics like Cowboy Bebop owe a debt to the road Akira paved. Hollywood took notes. Directors openly admit they cribbed ideas from it, weaving Akira’s DNA into blockbusters like The Matrix.

The influence spread wide. Kaneda’s iconic jacket, that red bike, the pill emblem—all became instant shorthand for rebellion. Today, you spot Akira’s fingerprints everywhere: fashion runways dripping in dystopian neon, music videos flashing with cyberpunk chaos, and video games offering crumbling cityscapes.

The phrase ‘Neo-Tokyo’ has even slipped into everyday genre slang, conjuring images of futuristic cities barely holding together. Akira’s footprint is not frozen in 1988. It keeps mutating, inspiring new artists, new visions, and reminding everyone that real revolutions leave scars across culture itself.

Why Akira Still Matters: A Warning Ignored

Even after all these years, Akira feels current. Its visions of unchecked technological madness, bloated political corruption, and crumbling identity do not feel dated. In an era where AI expands faster than we can manage and cities buckle under their own weight, Akira stands as a mirror, not a sci-fi warning.

Its influence seeps into modern storytelling. Trace its DNA through the Cyberpunk RPG, Ghost in the Shell, and any dystopian film featuring neon-soaked skylines. The tropes Otomo sharpened—power leading to self-destruction, technology amplifying human frailty, cities acting as living prisons—became the blueprints everyone borrows.

His take on characters like Tetsuo, whose grasp for strength turns him into something monstrous, shaped an entire generation of narratives. Today’s stories about mortals ascending to godhood, fuelled by hate and fear, owe a great deal to Akira’s brutal honesty.

Equally important, the visual language Otomo introduced established itself: gleaming monoliths towering over rotting alleyways, biker gangs roaring like a city’s anarchic heartbeat, technology dangling hope just out of reach.

Furthermore, its climax, a kaleidoscopic spiral of body horror and transcendence, smashed the idea that animation should play it safe. Animation could be violent, grotesque, beautiful, and terrifying all at once.

Kaneda was not some gleaming, perfect hero. He was messy, stubborn, and terrified—yet he fought regardless. His journey shows us that surviving the future means enduring the chaos, scars and all.

Conclusion: A Timeless Masterpiece

Akira endures because it refuses to compromise. It does not pat you on the head or offer easy answers. It grabs you by the scruff and hurls you into the void. Every frame, every sound, every narrative beat demands you sit up and pay attention. Even now, it feels like a living, snarling beast.

Moreover, its animation stands not just as technically brilliant but as viscerally felt. You live Neo-Tokyo’s collapse; you breathe it, and you taste the smoke in your throat. Countless films have attempted to copy its style, but few have managed to capture that raw, overwhelming energy.

Beyond the visuals, the storytelling cements Akira’s longevity. It neither spoon-feeds you morals nor holds your hand through its nightmare. Instead, it trusts you to get lost, to question, and to wrestle with what you see. Stories that dare to leave scars rather than deliver comfort—that is real artistry.

Its philosophical weight gives it layers that only grow heavier with time. Each rewatch reveals something new, whether a buried theme about identity or a grim warning about humanity’s arrogance.

Ultimately, Akira stands tall as a landmark of animation as a towering achievement in storytelling itself. Three decades later, its roar has not softened. It echoes louder now. True masterpieces burrow into culture’s bones.

Akira became part of the future it predicted.

Akira’s Author: Katsuhiro Otomo