Introduction: The Chemist’s Obsession

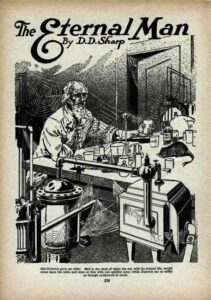

First appearing in the August 1929 issue of Science Wonder Stories (Vol. 1, No. 3), “The Eternal Man” by D. D. Sharp stands as a remarkably sophisticated example of early speculative fiction. Sharp’s narrative delves into the chilling consequences of scientific ambition. The plot follows Herbert Zulerich, a chemist whose solitary life is consumed by a singular, haunting goal: the eradication of death itself. Readers will find a narrative that feels unexpectedly modern, despite being penned nearly a century ago.

Plot Summary of "The Eternal Man"

Herbert Zulerich, a reclusive chemist, becomes obsessed with conquering death after witnessing the “appalling waste” of human mortality. Working alone in his laboratory, he conducts increasingly bizarre experiments on animals, attempting to unlock the secret of eternal life. His work leads him down a path of both scientific breakthrough and horrifying consequence.

Classical Tragedy and Compassion

Sharp crafts a cautionary tale that subverts the classic quest for immortality. Unlike Ponce de Leon’s mythical fountain or medieval alchemists’ philosopher’s stone, Zulerich’s discovery comes with a twist worthy of O. Henry—success becomes its own punishment. The story operates on multiple levels of irony: the man who sought to free humanity from death becomes death’s most complete prisoner, and the creature he blessed with eternal life becomes his eternal tormentor.

The narrative structure follows a classical tragedy arc. Zulerich’s hubris isn’t the typical scientist’s god complex; rather, it’s compassionate overreach. He genuinely grieves for humanity’s waste of potential, watching motor cars speed past his window carrying people rushing towards oblivion. This makes his fate more poignant than if he’d been motivated by ego or profit.

Gothic Science Fiction and Symbolism

The story belongs to gothic science fiction, blending laboratory horror with existential dread. Writing in 1929, Sharp was working in a genre barely three years old, yet already exploring mature themes that transcended simple adventure. Furthermore, the question-mark scar on the rat functions as perfect symbolism: Zulerich’s experiment poses questions he never answered.

The museum setting transforms Zulerich into a living artefact, a man literally frozen in 1929 who must watch the world change around him. The story’s forward-looking perspective—imagining “women scrambled with the male” in the workforce—shows Sharp anticipating social changes that would accelerate through the coming decades.

The child who pities the rat provides the story’s moral centre. Her instinctive compassion—wanting to end suffering rather than prolong existence—teaches Zulerich what his years of scientific study couldn’t: that quality of life matters more than quantity. This revelation arrives too late for action but not for understanding, making it both enlightening and tormenting.

Sharp’s tale builds on Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818), where scientific achievement yields unintended consequences. In addition, the story’s debt to Edgar Allan Poe is evident in its atmosphere and the theme of premature burial; though Zulerich suffers something worse than Poe’s narrators, a kind of eternal premature burial with full consciousness.

The Birth of Pulp Science Fiction

Published in 1929 in Science Wonder Stories Vol. 1, No. 3, the story emerged during a fascinating transitional period in American culture. The Roaring Twenties were reaching their peak—the same year would see the stock market crash in October, ending an era of unprecedented optimism and ushering in the Great Depression. The story’s references to motor cars speeding along highways and the general sense of people rushing through life captures the frenetic energy of the late 1920s perfectly.

This was also the golden age of pulp science fiction’s birth. Hugo Gernsback had founded Amazing Stories in 1926, and Science Wonder Stories (later merged into Wonder Stories) launched in June 1929 as part of Gernsback’s expanding science fiction empire. These early pulps were establishing the conventions and themes that would define the genre. Sharp’s story represents the more thoughtful, cautionary strain of early science fiction, contrasting with the more adventure-oriented space operas that dominated the era.

The 1920s saw remarkable scientific advances—the discovery of penicillin, advances in cellular biology, the beginning of modern genetics—that made the conquest of ageing seem tantalisingly possible. Yet the story also reflects on the rapid technological change. The motor car, still relatively new, symbolises both progress and recklessness in Zulerich’s observations of traffic rushing past his window.

Author: D.D. Sharp

D.D. Sharp remains an obscure figure in early science fiction, leaving little biographical trace. This appears to be one of few published works, typical of many contributors to early pulp magazines who wrote briefly before disappearing from the genre. Science Wonder Stories was Hugo Gernsback’s attempt to create a more scientifically rigorous magazine after losing control of Amazing Stories. The magazine emphasised plausible extrapolation from current science, making Sharp’s cellular biology-based premise particularly appropriate for its pages.

My Thoughts

I like to think how sophisticated this story feels for 1929, particularly given that science fiction as a named genre had barely been invented. Sharp demonstrates remarkable restraint. In lesser hands, this could have been purely shock horror focused on bodily grotesqueries. Instead, Sharp uses those elements sparingly, saving his real horror for the psychological and temporal. The image of Zulerich and the rat staring at each other for centuries, both unable to die, both in their own forms of agony, achieves genuine disturbing power through implication rather than description.

The motor car traffic streaming past Zulerich’s window serves as a brilliant recurring motif—in 1929, cars represented modernity, speed, and American prosperity. Having Zulerich watch this traffic for centuries emphasises both technological change and the unchanging nature of human mortality and folly.

The story’s ending demonstrates mature storytelling unusual for early pulp fiction. Rather than rescue or revenge, Zulerich achieves only wisdom—and wisdom that makes his situation more unbearable, not less. He realises his error but can do nothing about it.

Wrapping Up

The Eternal Man takes the fantasy of immortality seriously, following the premise to its logical, horrifying conclusion. The story suggests that death isn’t humanity’s curse but its mercy, and that consciousness without the possibility of change or conclusion might be existence’s cruelest form. Writing in 1929, at the dawn of both the Great Depression and science fiction as a distinct genre, Sharp created a work that goes beyond its pulp origins.

It addresses a perennial human obsession while offering no easy answers, only a chilling cautionary tale about the dangers of getting exactly what we think we want. For a genre still finding its voice, “The Eternal Man” demonstrated that science fiction could explore profound philosophical questions while delivering genuine horror—a lesson that would shape the genre’s development over the coming decades.

Other stories of Bad Chemistry

Another vintage pulp magazine:

Science Wonder Stories, Vol. 1, No. 2

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, Vol. 1, No. 1

Original Dynamic Science Fiction issue at the Internet Archive.

Disclaimer: The story featured on this page is in the public domain. However, the original authorship, magazine credits, and any associated illustrations remain the property of their respective creators, illustrators and publishers. This material is provided for informational and educational purposes only and may not be used for commercial sale.