Astounding Stories: The Roaring Start of Super-Science

You’re looking at the very beginning of a sci-fi revolution: Astounding Stories of Super-Science, Vol. 1, No. 1, hit news-stands in January 1930. This debut arrived at the height of the vibrant pulp magazine boom. Clearly, publisher William Clayton aimed for mass appeal, printing it affordably on cheap pulp paper. The magazine was priced at just twenty cents, which offered essential escapism for working-class readers during the Great Depression. Consequently, initial editor Harry Bates delivered high-octane spectacle—expect giant bugs, invisible horrors, and mad scientists galore.

Yet, Astounding harboured an ambition beyond mere sensationalism. Indeed, Bates actively pushed his writers to inject more genuine, plausible science into the thrilling plots. Therefore, this magazine stood slightly above its rivals, demanding a higher quality of speculative narrative. This crucial distinction allowed the title to bridge the gap between the wild early days of science fiction and the structured Golden Age. Furthermore, that bold editorial vision paved the way for future legends like Isaac Asimov and Robert Heinlein. Personally, compared to Amazing Stories and Science Wonder, this is the best Sci-Fi Pulp Fiction debut.

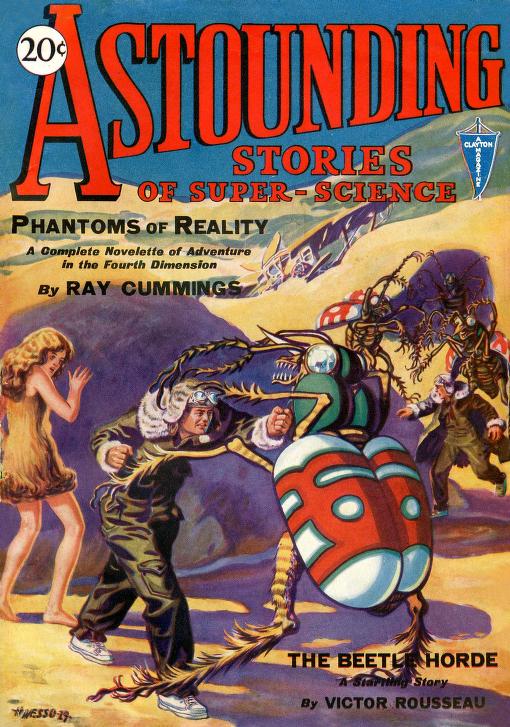

Cover Art: By Hans Waldemar Wessolowski (Wesso), depicting a scene from the lead story, “The Beetle Horde”. This visual emphasized giant monsters and pure action.

Full Contents of the Issue

"The Beetle Horde" by Victor Rousseau

An Antarctic expedition crashes through a storm into a hidden world beneath the Earth’s crust. Captain Storm, aviator Tommy Travers, and archaeologist Jim Dodd discover a civilisation of monstrous, highly organised beetles. Their survival adventure transforms into a desperate struggle against an evolutionary nightmare.

Read the full story here.

"The Cave of Horror" by Captain S. P. Meek

Strange disappearances in Mammoth Cave prompt government investigation. Dr Bird, a brilliant scientist, and Secret Service operative Carnes explore the caverns with experimental equipment. They hunt something unseen lurking in the darkness before more victims vanish.

Read the full story here.

"Phantom of Reality" by Ray Cummings

Wall Street clerk Charles Wilson joins his friend Captain Derek Mason on a dangerous mission. Derek has discovered a parallel dimension—a primitive world existing at a different vibratory rate. With political turmoil brewing and Derek in love with a woman from that realm, Charles must help prevent disaster across two realities.

Read the full story here.

"The Stolen Mind" by M. L. Staley

Owen Quest accepts a job from respected scientist Keane Clason, who claims his brother plans to sell a devastating weapon to foreign powers. Keane offers Quest money to stop Philip using the Osmotic Liberator—a device transferring consciousness between bodies. Quest soon realises he may have trusted the wrong brother.

Read the full story here.

"Compensation" by C. V. Tench

Professor Wroxton vanishes from his isolated estate alongside a mysterious visitor. The narrator investigates, finding only a strange crystalline cage and a diamond in the laboratory. Twenty years of cryptic experiments offer few clues to the reclusive scientist’s fate.

Read the full story here.

"Tanks" by Murray Leinster

During a future war fought beneath artificial fog, Sergeant Coffee and Corporal Wallis stumble upon intelligence that could determine a massive tank battle’s outcome. Their casual interrogation of a captured enemy infiltrator yields critical information, allowing their general to outmanoeuvre a superior force.

Read the full story here.

"Invisible Death" by Anthony Pelcher

Inventor Darius Darrow is murdered and his death weapon stolen. An extortion ring calling itself “Invisible Death” terrorises a wealthy corporation using the stolen technology. Objects fly through air, cars drive themselves, and criminals vanish before witnesses—making it appear the perfect crime.

Read the full story here.

The Pulp Context: Promise vs. Reality

Editor Harry Bates laid down an ambitious marker when Astounding Stories launched. His introductory editorial promised readers something distinctive: “Its stories will anticipate the super-scientific achievements of To-morrow—whose stories will not only be strictly accurate in their science but will be vividly, dramatically and thrillingly told.” This commitment to scientific rigour would eventually define the magazine’s reputation, though early issues didn’t always deliver on that lofty aspiration.

“The Beetle Horde” exemplified typical pulp fare—giant insects and melodramatic peril. However, “The Stolen Mind” demonstrated the magazine’s potential for something more meaningful. Instead of relying on another death ray or world-ending device, the story confronted readers with thoughtful questions about identity and consciousness (although it has a death ray). Dr Keane’s villainy wasn’t simply mad science spectacle; rather, it explored the terrifying possibility of having one’s very self stolen.

The magazine was finding its voice through this tension between pulp entertainment and thoughtful speculation. Moreover, readers were getting both thrills and substance, even if the balance shifted issue by issue. Stories flipped familiar tropes by grounding fantastic premises in psychological stakes rather than pure action. This approach distinguished Astounding from its competitors, gradually building the reputation Bates had promised from the beginning. Not at all, actually, but, you’ll feel some differences when you read this and compare it to Amazing Stories, for example

.

The Depression's Shadow and Greed as Villain

The Great Depression cast a long shadow over 1930s America. Following the October 1929 stock market crash, financial anxiety permeated daily life across all social classes. Astounding Stories offered escapism at twenty cents per issue—an affordable refuge for working-class readers during economically brutal times. This cheap price point represented vital access to entertainment when luxuries had become unaffordable.

Readers could vicariously experience adventures, power, and agency that reality denied them. Furthermore, the fantastical settings allowed temporary forgetting of breadlines and evictions. These magazines acknowledged implicitly that people needed affordable dreams during their darkest hours, delivering them consistently month after month.

Pre-Atomic Doom and the Spectre of Mass Destruction

World War I had fundamentally altered humanity’s relationship with violence. The conflict introduced industrial-scale killing, producing roughly 15 to 22 million total casualties—military and civilian combined. Chemical weapons, machine guns, and artillery demonstrated that technology could amplify destruction beyond previous imagination.

“The Stolen Mind” envisioned a weapon with a 500-mile kill radius. This wasn’t fanciful speculation but logical extrapolation from recent history. Readers in 1930 understood that super-weapons weren’t science fiction fantasies—they were inevitable developments. The question haunting the public consciousness wasn’t if such weapons could be built, but when and who would build them first.

The Launchpad to the Golden Age

Harry Bates’ editorial vision planted seeds that would transform science fiction forever. His tenure lasted only until 1933, when publisher Clayton went bankrupt during the Depression’s depths. However, the magazine’s promise hadn’t died—Street & Smith purchased the title and appointed F. Orlin Tremaine as editor.

Tremaine continued refining the formula, but the real revolution came in 1937. John W. Campbell, Jr. assumed the editor’s chair and built upon the foundation Bates had established. Campbell’s demand for rigorous scientific speculation and character-driven narratives emerges from Bates’ original promise of “strictly accurate” science combined with thrilling storytelling.

The Golden Age of Science Fiction flowered under Campbell’s guidance. Isaac Asimov, Robert Heinlein, and A.E. van Vogt found their platform within Astounding’s pages, pushing the genre towards sophisticated examinations of future societies and technological possibilities. These authors could experiment with complex ideas because Bates had already proven the market existed for thoughtful speculation wrapped in accessible adventure.

Astounding Stories of Super-Science in 1930 was that crucial first step—action-packed yet ambitious, entertaining whilst reaching for something more substantial. The magazine demonstrated that readers craved thrills alongside ideas, escapism intertwined with intellectual challenge. Again, I like this issue and think it carries so many valuable moments, stories and ideas.

Another vintage pulp magazine:

Science Wonder Stories, Vol. 1, No. 2

Original Astounding Stories issues at the Internet Archive