Para o texto em Português, clique Aqui.

Introduction: The Irony of Almost Giving Up on a Classic

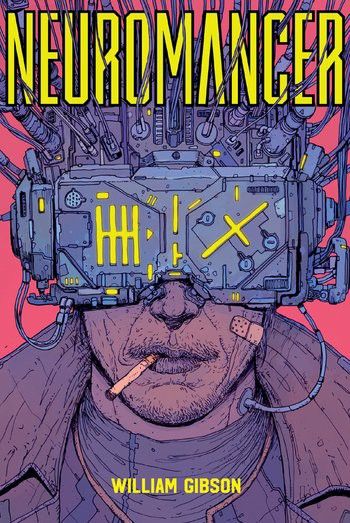

It’s intriguing to note that Neuromancer, along with the entire Sprawl trilogy, ranks among the finest books I’ve ever had the pleasure of reading. And yet, there was a moment when I nearly gave up on it. The irony becomes all the more striking when one considers that Neuromancer is not merely a work of fiction; it’s a seminal piece that redefined the cyberpunk genre and became a cultural landmark, influencing not just literature, but also cinema, video games, and popular culture at large. That’s why, whenever I reflect on Neuromancer, I’m overcome by a conflicting feeling: there are so many facets I’d like to explore, and yet, when I try to organise my thoughts, I find myself at a complete loss as to where to begin.

What compels me to delve into this work is the curious paradox it presents in my own experience: it wasn’t a book that gripped me from the outset, but somehow, its complexity and depth won my admiration over time. Let’s just say I didn’t enjoy reading Neuromancer, but I’m immensely glad to have read it.

The Relevance of "Neuromancer" to Cyberpunk and Pop Culture

The Sprawl trilogy, comprising Neuromancer (1984), Count Zero (1986), and Mona Lisa Overdrive (1988), is set in a dystopian future where technology and corporations wield absolute power. Society sinks ever deeper into increasingly alienating and hallucinatory experiences, while the line between man and machine grows ever more blurred. It is within this dark and kinetic backdrop that we are introduced to a cast of complex and decaying characters, most of whom win us over with their charisma and eccentricity.

One might say that Neuromancer is to cyberpunk what Treasure Island is to pirate stories. Just as Stevenson shaped the image of pirates in popular culture, Gibson established the tropes and conventions that continue to define cyberpunk to this day. Although the Sprawl trilogy wasn’t the first cyberpunk work, it undoubtedly stands out as the most iconic example of the genre. Its dystopian vision of a future ruled by megacorporations, coupled with the pervasive presence of technology, showcases Gibson’s uncanny ability to anticipate social and technological trends. Published in 1984, the book predicted concepts such as the internet, artificial intelligence, cybernetic implants, and virtual reality—decades before they came to pass. All of it portrayed through a lens that is as cynical as it is precise.

An Overview of the Sprawl

Before delving into an analysis of Neuromancer, it’s important to place the novel within the context of the Sprawl trilogy. Although I’ll be focusing solely on the first book, I’ve included an outline of the trilogy below. Many readers are unaware that Neuromancer is part of a larger universe.

Neuromancer:

The starting point of the series introduces us to Henry Dorsett, better known as “Case,” a hacker who has lost the ability to access cyberspace after betraying his employer. Recruited by Molly and Armitage, he embarks on a mission to infiltrate the corporate empire of Tessier-Ashpool, located in orbit.

Count Zero:

The second book weaves together three interlinked storylines. The first follows Turner, a former mercenary hired to facilitate the illegal defection of a Maas Biolab employee to rival company Hosaka.

In the second narrative, we meet Marly, a former art curator who is recruited by the reclusive billionaire Josef Virek to track down the creator of a series of mysterious boxes.

Finally, we follow the story of Bobby Newmark, also known as Count Zero, who becomes involved with a group seeking to unravel the mystery behind the emergence of voodoo deities within cyberspace.

Mona Lisa Overdrive:

The trilogy concludes with Mona Lisa Overdrive, following the same structural approach as its predecessor, presenting four distinct yet interconnected storylines.

The first introduces Kumiko, a young Japanese girl whose path leads her to London as she flees the gang wars involving the Yakuza.

The second follows Slick Henry, a former car thief tasked with looking after Bobby Newmark, who has fallen into a coma after jacking into cyberspace.

The third narrative brings back Angie Mitchell, now a cyberspace celebrity with a unique ability: she can access the matrix without the need for a deck (computer) and communicate directly with the artificial intelligences that inhabit the virtual world—thanks to modifications made to her nervous system by her father.

Lastly, we meet Mona, a teenage prostitute who finds herself caught up in a kidnapping plot, forced to undergo surgery that will turn her into a replica of Angie Mitchell.

A word of warning: from this point onward, there may be minor spoilers and revelations concerning key parts of the story.

The Story of "Neuromancer": A Dive into Cyberspace

Essentially, the plot of Neuromancer is a heist story: a group of characters comes together to plan the infiltration of an impenetrable fortress, facing challenges and twists along the way.

The novel introduces us to Henry Dorsett Case, a talented hacker who has lost his ability to access cyberspace after betraying his employer. As punishment, he was injected with a neurotoxin that damaged his nervous system, leaving him unable to connect to the matrix — the virtual world navigated by hackers like himself.

Now, Case lives on the fringes of society in Night City, a chaotic and violent metropolis where he scrapes by through petty scams and illicit jobs.

Everything changes when he is recruited by Molly Millions, an enigmatic razorgirl equipped with cybernetic implants that make her a deadly combatant, and Armitage, a mysterious figure who offers to restore Case’s ability to access cyberspace in exchange for his services. The mission? To infiltrate the Tessier-Ashpool empire — one of the world’s most powerful megacorporations — located aboard a space station called Villa Straylight.

Complex and Decadent Characters

One of Neuromancer’s greatest strengths lies in its characters, who are every bit as complex as the world they inhabit.

Case, the protagonist, is a skilled hacker, but his life is a portrait of decay, steeped in depression and drug dependency. He is no hero — not even an anti-hero — but rather a mercenary who, strangely enough, manages to captivate us. He shows little sense of self-preservation and seems perpetually on the brink, entangled in alcohol and shady dealings. Case is precisely what one expects from a cyberpunk lead: morally ambiguous, deeply flawed, and unmistakably human. His is a brutal authenticity, born of the chaos of a dystopian reality.

Molly, the enigmatic razorgirl, is another standout in the story. Enhanced with cybernetic implants — including retractable blades in her hands and mirrored lenses in place of eyes — she embodies the very essence of “badass”. Her past remains shrouded in mystery, and her relationship with Case (and with us, the readers) is deliberately kept at arm’s length, leaving us eager to uncover more about her.

Armitage, the leader of the trio, holds the knowledge about the mission and the resources required to see it through. He is the operation’s strategist, directing the team while keeping his own motives and true nature hidden from view.

Another memorable figure is Dixie Flatline, the preserved consciousness of a hacker stored within an artificial intelligence simulation. His dry wit and seasoned perspective make him a compelling character. Acting as Case’s mentor, Dixie is constantly offering cheeky, sardonic guidance.

The Finn is an eccentric but charismatic tech dealer — the sort of bloke who always knows someone. His role may be brief, but he leaves a lasting impression.

And then there’s Riviera — the team member no one likes, neither the characters nor the readers. With his unstable personality and questionable motives, he acts as a disruptive force within the group, heightening the tension that runs throughout the narrative.

The Creation of the Cyberpunk World

Gibson crafts a dystopian future that is as fascinating as it is terrifying. Night City is a place where cutting-edge technology coexists with human ruin. He immerses the reader in a world that reeks of burnt oil, where neon lights blaze endlessly. It’s a sensation of despair and alienation — everything, including life itself, feels cheap and transient.

Cyberspace is one of Neuromancer’s most revolutionary concepts. Gibson famously describes it as a “consensual hallucination” — a virtual realm where hackers like Case dive in to steal data, breach systems, and conduct covert operations. Yet cyberspace is just as much a threat as it is a frontier. It’s guarded by lethal security constructs, hostile AIs, and other dangers capable of frying an unprepared hacker’s mind. For Case, cyberspace is both a cage and a kind of liberation.

The cyberpunk aesthetic is simultaneously futuristic and decaying, merging high technology with a deep sense of wear and erosion. The cold glow of screens against the darkness of alleys, even the minimalist elegance of the Villa Straylight, all contribute to a visual language that is both powerful and transcendent.

This interplay of light and shadow reflects the promise of a brilliant technological future set against the grim reality of social inequality.

The visual identity of cyberpunk in Neuromancer is also defined by the fusion of the organic and the technological. Technology becomes an extension of the human body. When Case jacks into cyberspace, he experiences the interface as an extension of his very own nervous system.

The Challenges of Reading "Neuromancer"

Despite all the praise, Neuromancer is not an easy read. The density of the world Gibson has crafted — filled with intricate technologies and a hyper-globalised culture — can feel disorienting. The author makes no effort to explain every detail, which lends the work a strong sense of authenticity, but also demands more from the reader.

Moreover, the extended narrative, lengthy dialogues, and meticulous language can make the reading experience quite exhausting. Connection with the characters also varies; not everyone will relate to the eccentricity of Case, Molly, or Dixie Flatline. For some, Molly’s apparent emotional detachment or the abstract nature of Dixie might be off-putting.

And, to be honest, I’m not sure it gets any easier as the story progresses.

The novel suffers from a temporal dilemma — in truth, all classics do. As new works are created, inspired by or directly influenced by the originals, the elements that were once groundbreaking can start to feel overly familiar. When we return to the source, there’s often a sense of disappointment, as if nothing feels truly new.

The Challenge of Visualising Cyberpunk

One of Neuromancer’s greatest hurdles is the sheer difficulty of visualising its world. Cyberpunk, as a genre, often thrives in visual mediums like films and graphic novels. In Neuromancer, the task of imagining every detail falls entirely on the reader — and that can be exhausting. The lack of clear descriptions and the complexity of its concepts make reading a challenging experience. Reading is an active task — the author doesn’t draw the world for you, he gives you guidelines so you can sketch it yourself. And if that process requires too much effort, the chances of abandoning the book increase. That’s how I felt reading Neuromancer — like I was trying to draw something complex, most of it ending up skewed and unfinished.

In Retrospective

Despite everything, I now look back on this book fondly — with a renewed appreciation for its details, its atmosphere, its striking scenes, and its utterly mad concepts. Everything feels so organically interwoven, the result of masterful craft. All the reasons I once considered giving up feel distant now. Reading is, undeniably, something we learn — a journey of self-improvement.

Neuromancer is a work that rewards those who endure. In hindsight, I see Case as the legendary cyberpunk icon that he is, and Molly as the embodiment of resilience in a chaotic world. The read may not have been easy, but it was profoundly rewarding. This book has given me valuable lessons; I still turn to it for insights into Gibson’s techniques. Having solid references is crucial for creative growth.

Perhaps you’re not a writer. Maybe you don’t even enjoy reading. It truly doesn’t matter what you do or want to do — we all encounter certain stories that are difficult to get through. I hope that, in some dystopian future, you too can look back and say: “It wasn’t good to read, but it was good to have read.”

Well, that’s all for now!