Who Was Spring Heeled Jack?

Spring Heeled Jack remains an intriguing and “frightening” character within English folklore. He first appeared in London during the Victorian era at the start of the nineteenth century and caused panic amongst residents in urban and rural districts. Witnesses described a humanoid figure with the power to perform immense leaps, and he fast became a popular legend.

In addition, although Spring Heeled Jack began as a figure of urban folklore, his true fame grew once the legend migrated to the “penny dreadfuls” and popular pamphlets of nineteenth-century England. This process occurred often during the Victorian era, as writers adapted grim stories to meet the rising demand for cheap entertainment.

Furthermore, reports varied, but many agreed on grim details: Spring Heeled Jack wore a dark cloak, possessed eyes that glowed like fire and, in some cases, featured sharp claws on his hands. His name soon spread across the whole of England. Oral accounts, full of exaggeration and mystery, provided the perfect material for writers who sought to grip the public’s attention. Thus, Spring Heeled Jack ceased to be a mere street rumour and instead existed as a literary character.

The Historical Context of Victorian England

The Victorian era saw rapid social changes. Growth in the cities, urban poverty and a rise in crime created a climate of fear at all times. In such a setting, tales like that of Spring Heeled Jack found fertile ground.

The sensationalist press of the time helped to amplify the panic through the publication of exaggerated reports and grim illustrations. This transformed Spring Heeled Jack into an almost mythical figure, as fact blended with popular imagination.

Regional newspapers printed contradictory accounts, letters from readers and rumours without any cohesive narrative. Such a trend occurs often in these events, where people describe the creature in different ways with unclear intentions. In other words, writers just attributed isolated cases to a single figure.

The Birth of a Nightmare: 1837-1838

The first documented report emerged in October 1837. At that time, a creature attacked Mary Stevens, a young servant girl, as she crossed Clapham Common. The figure that stepped from the dark fit no known category. In her account, she spoke of hands “as cold and clammy as those of a corpse” and mentioned metal claws. Furthermore, the creature showed a ritualistic rather than violent nature. Instead of murder or theft, the figure tore her clothes, kissed her face in a rough manner, and fled once others arrived. The theatrical nature of this case makes it stand out.

A few months later, on 19 February 1838, Jane Alsop experienced the encounter that would define the legend. A man knocked on her door and claimed to be a police officer who had captured Jack and required a candle. Once she brought the light, he cast off his cloak to reveal a grotesque figure. Jane noted eyes that glowed like “red balls of fire” and a mouth that spat blue and white flames. In addition, the attacker wore a helmet and a tight-fitting suit. He launched a brutal attack — he tore her clothes and scratched her skin — yet once more, he made no attempt to take her life.

The case of Lucy Scales, one week later, followed a similar pattern. The figure rose from the shadows and spat blue fire into her face. This act caused a temporary loss of sight. After this, he vanished with impossible leaps.

Henry Beresford: The Aristocrat as an Archetype of Chaos

Henry de la Poer Beresford, 3rd Marquess of Waterford, stands as a prime earthly candidate for Spring-heeled Jack. The public dubbed him the “Mad Marquis”. Here the story gains true interest, for Beresford did not act as a common psychopath. Instead, he served as a perfect symbol for the contradictions of the Victorian aristocracy.

In April 1837, Beresford and his friends arrived at Melton Mowbray in a drunken state. They “painted the town red” in a literal sense — the origin of the famous idiom. They attacked a guard, stole red paint from building sites, and covered doors, windows, and even people across the town in it. This did not represent an isolated case. His “pranks” included: the staging of horse chases, the placement of chimney sweeps inside a first-class carriage, and a raid on Eton to steal a teacher’s birch.

Witnesses reported the sight of the Beresford family crest on the attacker’s clothes. Furthermore, Jack’s attacks in 1837-38 coincided in a geographic sense with the known locations of Waterford. One newspaper from 1838 described him as “that turbulent piece of aristocracy”. It claimed that people held his name in as much dread as Spring-heeled Jack himself.

Yet a twist exists in the tale. Waterford married Louisa Stuart in 1842. From that point on, he gained a respectable reputation and settled in Ireland until his death in a riding accident in 1859. Nonetheless, Jack’s attacks continued for decades. In 1870, he terrorised sentries in Aldershot. In 1877, crowds in Lincoln shot at him — he just laughed and leapt over buildings to escape. The final report with broad documentation comes from Liverpool in 1904.

The Social Psychology of Panic

Spring-heeled Jack did not emerge in a vacuum. Victorian England in 1837 acted as a cauldron. London transformed from a medieval city into an industrial metropolis in a matter of decades. Factories rose, masses moved from the countryside to urban ghettos, and the traditional social landscape fell apart. Jack represented this monstrous change — a blend of the medieval (a demon with flames) and the modern (metal helmets, mechanical devices, industrial clothes).

Furthermore, Jack’s powers — coloured flames and impossible leaps — hinted at technology beyond common grasp. In an age of steam, the telegraph and photography, the future looked both wondrous and full of dread.

In addition, most victims comprised young women from the working class — servants, seamstresses and shop girls. In contrast, suspects tended to be bored aristocrats. Victorian newspapers found that terror and sensationalism sold well. Each attack by Jack led to a vast surge in sales. These stories fed back into the cycle — reports sparked copycat attacks, which gave rise to more headlines. This process created more fear, which in turn produced further sightings.

The Role of Penny Dreadfuls

Penny dreadfuls consisted of cheap publications sold for a penny, often in the form of weekly chapters. These tales targeted young folk from the working class and mixed horror, crime and sensationalism. To view penny dreadfuls as “sensationalist rubbish” repeats a Victorian prejudice, as people saw them as a cheap alternative to literature.

Spring Heeled Jack fit this format to a tee alongside characters such as Sweeney Todd and Varney the Vampire. All these figures combined horror and melodrama. His grim look, supernatural skills and erratic conduct ensured constant suspense and high sales.

These pamphlets enjoyed great fame among teenagers and young adults. Many parents and teachers attacked the content and claimed it encouraged immoral deeds. Yet, this row just boosted public interest.

“Spring-Heel’d Jack: The Terror of London”

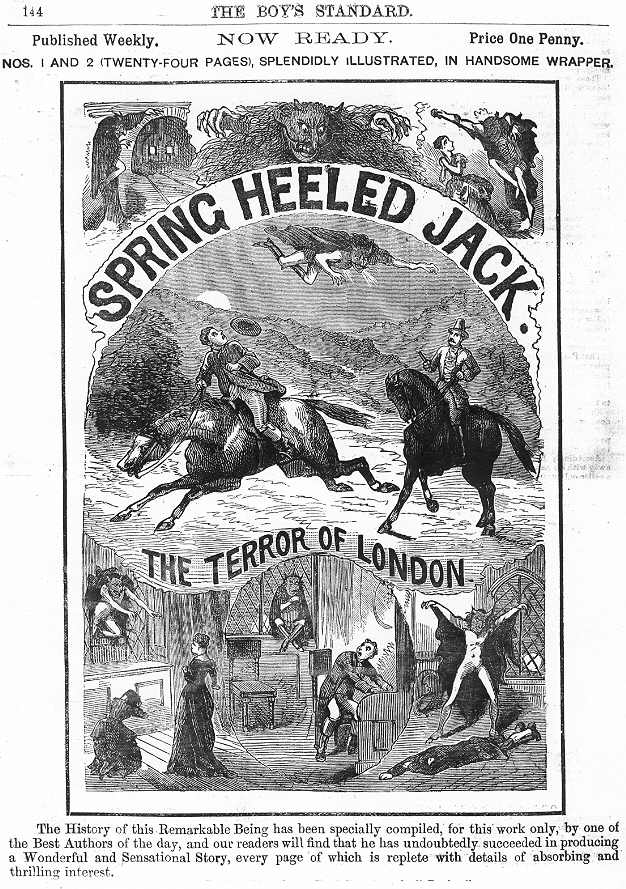

The most famous pamphlet about Spring Heeled Jack went to print between 1840 and 1841 under the title “Spring-Heel’d Jack: The Terror of London”. This work played a vital part in the definition of the character as a staple of popular literature.

As a rule, people credit Thomas Peckett Prest as the author, though academic debates on the matter persist. Prest held a reputation for the creation of sensational stories, often based on real crimes and urban myths.

In the pamphlet, the writer depicts Spring Heeled Jack as more than just a typical folk monster. Instead, he presents a more complex character entangled in plots, crimes and acts of revenge.

From Villain to Anti-Hero

In a curious turn, some literary versions did not present Spring Heeled Jack just as a villain. At times, he took the role of an anti-hero and punished criminals even worse than himself. Authors today use this same device as a common rule in books and film — the rewrite of a legend.

After the success of the original pamphlet, various writers reused the character or created alternative versions. Some tales turned him into a clever criminal, whilst others portrayed him as a supernatural creature.

One aspect in particular reveals much about these narratives: the push to offer rational explanations for things which newspapers described as supernatural. Impossible leaps cease to be the work of demonic forces and instead link to mechanical gadgets. The fire from his mouth becomes a chemical trick. Metal claws turn into artificial devices. Thus, he appears less as a demon and more as an extreme product of the modern age.

Appearance and Supernatural Skills

The descriptions of Spring Heeled Jack were wild indeed. Witnesses claimed he could leap over high walls and roofs with ease, a feat beyond a normal human in those days. In theory, he had springs in his feet. Furthermore, talk spread of flaming eyes and metal claws on his hands, plus a shrill and terrifying laugh. In short, he possessed all the traits to scare an average person in Gothic England.

By 1900, Jack became tame in another way — a bogeyman to frighten children. Victorian parents used the threat: “If you do not behave, Spring-heeled Jack will jump through your window at night”.

But the twenty-first century rediscovered Jack through the steampunk look. With the passage of time, the character broke free from his specific tales and survived as an archetype. The figure of a masked, urban individual with advanced tech and unclear morals finds clear echoes in later pulp literature, comics and even cinema.

The Dark Mirror of Modernity

In the end, Spring-heeled Jack evaded capture because he was not a person — he acted as a symptom. He represented a symptom of a society in the midst of a radical shift so vast that people could only process it through the fantastic and the grotesque.

When we look at Jack in depth, we see all the contradictions of Victorian England: a nation that took pride in scientific reason whilst it remained obsessed with the supernatural; a society that preached Christian morals whilst its elite practised cruel acts without fear; a culture that cheered industrial progress whilst it feared the results.

He acted as the collective unconscious leaping over the roofs of London. Sixty-seven years of sightings. No capture. No firm physical proof. Just terror, charm and the sense that something at its core beyond explanation touched the neat reality of Victorian England.

Books and pamphlets proved vital to transform Spring Heeled Jack from a mere urban rumour into a lasting icon of English popular literature. Through a mix of terror and social critique, these works ensured the legend crossed generations and remained alive in the shared mind of the public.