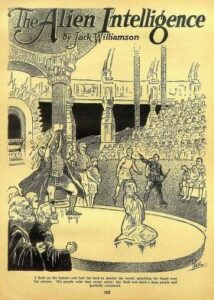

A Vision of Early Pulp

“The Alien Intelligence” is a classic pulp sci-fi that reads like a fever dream meets a travelogue. Williamson throws everything at the wall—lost worlds, crystal cities, purple monsters, and physics-defying metal lakes—and somehow the mixture works. The prose carries that breathless, adjective-heavy style of early pulps which proves either charming or exhausting. Ultimately, this story defined the “sense of wonder” for an entire generation before the genre learned subtlety, and while every idea remained big, weird, and urgent.

Plot Summary of The Alien Intelligence

Dr Winfield Fowler travels to the Australian outback after he receives a radio signal from his missing friend, Horace Austen. Horace claims he is trapped in a “world of alien terrors” inside a crater known as the Mountain of the Moon. Driven by fear, loyalty, and the hope that Horace survives, Fowler sets out at once to uncover the truth.

Striking Visuals and High Imagination

In this setting, Williamson’s imagination operates at full throttle. The set pieces possess a genuine power: for instance, during the first night, glowing red shapes wheel through darkness like predatory moths around Astran’s defensive beam. Later, a sky-ladder forms—a miles-long silver cylinder that spins coloured rings and drops liquid metal into the lake. This sight nearly drives Fowler insane. Furthermore, the crystalline city catches sunlight in prismatic fire, adding to the visual feast.

Surprisingly, the horror elements hold up well. The pursuit by the first “Purple One”—which keeps coming despite multiple wounds while emitting an awful inhuman laugh—delivers genuine tension.

Scientific Earnestness, Romance and Social Context

The science babble contains a charming earnestness. Fowler actually analyses the Silver Lake with test tubes and spectrometers, and he records specific gravity while noting its corrosive properties. Although the logic is nonsense, it is detailed nonsense.

In contrast, Fowler’s personality offers little more than a mannequin holding a rifle. He exists to observe and shoot things. His “love” for Melvar happens because the genre demands it; he tries to kiss her within minutes of meeting, she flips him (rightly so), then suddenly they are in love. Because the romance lacks psychology, it feels like a mere plot obligation.

The racial politics reflect their era. The “magnificent” white-skinned Astranians stand against the “savage” purple beings, implying that true civilisation requires European features. Moreover, Melvar’s people appear simultaneously advanced (synthetic diamonds!) and primitive (no fire!), a contradiction that serves the “noble savage” trope.

Pacing and Prose Style

However, the pacing remains erratic. We sprint through a purple monster attack, then halt for three paragraphs about cycad evolution and atmospheric pressure. Williamson seemingly cannot decide if he is writing adventure or hard-SF speculation. Furthermore, the prose overdoes everything. Every cliff is “precipitous,” every emotion “terrible,” and every sight “vast.” After a while, the adjectives cancel each other out. To be fair, this was the house style for pulps, as editors demanded excitement on every page.

The Tragedy of Astran

Thematically, Astran acts as the story’s beating heart. This society once synthesised diamonds, built soaring architecture, and understood advanced physics—yet they lost it all. Now, they maintain one defensive weapon they cannot repair. While the city crumbles, they simply pick fruit. It represents a nightmare of cultural decline: a people surrounded by the achievements of their ancestors, unable to recreate them, and slowly forgetting such feats were even possible.

WWI had shown how quickly “civilised” Europe could collapse into barbarism. In the story, religion replaces science and curiosity becomes heresy. The priests of the Purple Sun suppress Austen’s knowledge of the outside world because it threatens their authority. Consequently, ignorance becomes a tool for institutional power.

Author: Jack Williamson

Author Jack Williamson works in the “lost world” tradition of H. Rider Haggard and Arthur Conan Doyle. Yet, he technologises the concept. This is not Atlantis or a land of living dinosaurs; instead, it is parallel evolution creating genuine alienness on Earth. The Astranians appear human but are not quite right, while the Purple Ones demonstrate something worse than death.

The story bridges Victorian adventure fiction and modern SF. Fowler’s journey echoes colonial exploration narratives where a brave man penetrates savage lands to save a princess. However, the tech elements point forward: rocket propulsion, death rays, and genetic transformation. Williamson sits trapped between pulp conventions and genuine speculative ambition.

As this is Part One, it creates an interesting effect—the story leaves us in the heart of the mystery with answers tantalisingly close. The mist-shrouded land beyond the lake becomes pure potential, reflecting whatever terrifies and fascinates us most.

My Thoughts

While this is comfort food sci-fi, it hides surprising nutrients within the cheese. Yes, it is dated, and Fowler is a cardboard hero. Yet, when Fowler watches the sky-beam and feels an alien intelligence seizing his mind, the story achieves good horror.

The Purple Ones haunt me more than expected. The implication that they are transformed humans—victims of the Krimlu who return as unkillable hunters—presents body horror decades ahead of its time. They are victims and monsters simultaneously.

Above all, I admire Williamson’s earnestness. At twenty-one, writing for a penny-a-word, he truly tries. He provides careful scientific analysis and detailed descriptions of architecture. He even attempts to give Melvar a personality beyond “pretty native girl” by having her read Tennyson and question authority. He clearly cares about this world.

Modern readers might smirk at the purple patches in the prose, but one finds value in that unironic enthusiasm. These writers believed science fiction could inspire real progress. They saw themselves as visionaries.

Wrapping Up

The Alien Intelligence is flawed, dated, and occasionally ridiculous—yet it remains genuinely imaginative. Even at a young age, Williamson understood that great sci-fi makes you feel the alienness before explaining it. It is not a perfect story, but it is a perfect artifact. It captures an era when science fiction was inventing itself and when every story might contain the idea that changes everything. We could use more of that optimism today.

Other stories from Science Wonder Stories Vol 1, N° 2 (1929)

The Boneless Horror

More Works:

Another vintage pulp magazine:

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, Vol. 1, No. 1

Original Science Wonder Stories issues at the Internet Archive

Disclaimer: The story featured on this page is in the public domain. However, the original authorship, magazine credits, and any associated illustrations remain the property of their respective creators, illustrators and publishers. This material is provided for informational and educational purposes only and may not be used for commercial sale.