Introduction

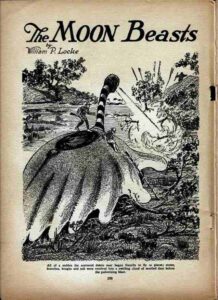

First appearing in the August 1929 issue of Science Wonder Stories, “The Moon Beasts” is an example of early hard science fiction. William P. Locke offers a grounded, methodical exploration of an extraterrestrial encounter. The year 1929 represented a peak for “scientifiction” before the economic hardships of the 1930s took hold. Readers of the time were hungry for stories that combined the spirit of exploration with the advancements of the industrial age.

Plot Summary of "The Moon Beasts"

Joseph Crawford and his friend Barry Edwards embark on a fishing holiday in the Canadian wilderness, only to witness a mysterious object crossing a lake at night, leaving devastation in its wake. Their curiosity leads them on a grueling five-day trek through swamps and forests as they follow a strange trail of disintegrated vegetation. What they eventually discover challenges everything they understand about life on Earth.

First Contact Hard Science Fiction

Locke constructs what might be called “first contact hard science fiction,” grounding his fantastic premise in plausible biological and physical mechanisms. The story progresses through a methodical revelation. Crawford and Barry approach the mystery as scientists, testing hypotheses and making observations before jumping to conclusions. At first, they assume they are tracking a secret aircraft. This theory gradually gives way to the realisation that they have encountered something far stranger. Detailed descriptions of the creature’s biology demonstrate imaginative effort rather than vague hand-waving about “alien technology.”

The narrative structure employs a frame story, with Crawford recounting his experience to Stewart. This serves multiple purposes. To begin with, it provides credibility through corroboration regarding Stewart’s New Guinea trail. In addition, it allows for reflective commentary on the events and creates dramatic irony as the reader knows more than Stewart does. The framing also permits Locke to skip tedious travel details while keeping the narrative pace brisk.

The moon-beasts themselves represent a biological speculation for 1929. Locke imagines creatures that are essentially living machines, complete with organic solar panels, biological projectors, and matter-disruption weaponry.

Alien Invasion

The story belongs to what we might call “invasion prehistory.” It is not quite an invasion story since only three scouts arrive, yet it establishes the threat of future colonisation. Locke works with the “ancient astronauts” trope that appears in works from H.P. Lovecraft to Erich von Däniken. Even so, Locke’s version involves recent rather than ancient visitations.

The moon-beasts embody what critic John Clute calls “the exhaustion motif” in science fiction—civilisations that deplete their resources and must expand or die. These beings are not evil but desperate. One might view them as refugees rather than invaders, though the distinction matters little to potential victims.

Locke’s biological approach to alien life contrasts with H.G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds (1898), where Martians use mechanical tripods rather than being biological equivalents. His creatures more closely resemble those in Edgar Rice Burroughs’s planetary romances, albeit with far more scientific rigour. On top of that, the perforated trail and calcified fish echo biblical plagues, suggesting Locke may have drawn on Exodus imagery. The creatures function as anti-life, converting the organic to inorganic and the living to dead.

Author: William P. Locke

William P. Locke remains another obscure figure from early pulp science fiction. “The Moon Beasts” appears to be his only significant work, yet it demonstrates considerable skill in pacing, description, and scientific extrapolation. The competence of the prose suggests Locke may have had scientific training. This is evident in his accurate rendering of spectroscopy principles and careful attention to physical plausibility.

Hugo Gernsback’s Science Wonder Stories specifically sought tales that balanced adventure with scientific accuracy. Locke delivers exactly that. He provides thrilling encounters while grounding his fantastic creatures in quasi-plausible biology. What is more, the magazine’s emphasis on “science wonder” rather than pure adventure explains why Locke’s methodical approach fit so well.

My Thoughts

Unlike many pulp stories that rush to action, “The Moon Beasts” spends nearly half its length on the tracking journey. This builds atmosphere and allows wonder to accumulate. The ending, with Stewart’s New Guinea expedition providing corroboration, transforms a fantastic tale into something more unsettling. By placing Crawford’s account in a larger context, Locke suggests these events happened within his fictional universe. Final lines about an “exciting hunt after most peculiar game” promise sequels that never materialised, leaving the other moon-beasts unaccounted for.

The story’s one weakness is characterisation. Crawford and Barry function more as observers than fully realised people. Their witty banter feels somewhat artificial, and Jules exists primarily as comic relief. Perhaps this is intentional. Locke focuses on the alien encounter itself, treating human characters as witnesses rather than protagonists.

The story also works as an environmental parable without being didactic. Locke shows what happens when a species exhausts its resources and must exploit new territory. In effect, the moon-beasts have eaten their world into a pockmarked corpse.

Wrapping Up

Locke takes his premise with total seriousness and follows its implications to the end. Rather than dismissing the mechanics of his creatures, he imagines them as biological organisms adapted to lunar conditions. He then explores how they would function in the different environment of Earth.

Writing in 1929, Locke could not have known that within forty years humans would visit the Moon and find it lifeless. His speculation represents a last gasp of pre-space-age planetary romance. In that era, other worlds might still harbour anything the imagination could conjure.

Another vintage pulp magazine:

Science Wonder Stories, Vol. 1, No. 2

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, Vol. 1, No. 1

Original Science Wonder Stories issue at the Internet Archive.

Disclaimer: The story featured on this page is in the public domain. However, the original authorship, magazine credits, and any associated illustrations remain the property of their respective creators, illustrators and publishers. This material is provided for informational and educational purposes only and may not be used for commercial sale.