Consciousness Transfer Science Fiction

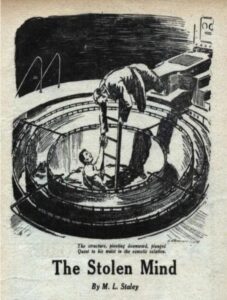

“The Stolen Mind”, written by M. L. Staley and published in Astounding Stories of Super-Science, delivers a story about mind transfer. The tale follows a fast and unsettling sequence of events involving identity, betrayal, and scientific ambition. The Stolen Mind appeared in the magazine’s very first issue in January 1930. The idea still feels bold today, yet it must have seemed even stranger at the time.

Plot Summary of The Stolen Mind

Owen Quest, a young man seeking quick money, answers an unusual job advertisement from the respected Clason Research Corporation. Keane Clason, the company’s head, claims he has built two remarkable machines: a destructive weapon called the Death Projector and another device named the Osmotic Liberator. He insists his brother Philip plans to sell the weapon to a foreign power, which could trigger a global disaster. Keane offers Quest a generous payment to stop Philip by using the Osmotic Liberator, a device that supposedly transfers a person’s consciousness into another body. Quest accepts the offer, although he soon realises he may have trusted the wrong brother and stepped into a trap he never imagined.

1930's Pulp Science Fiction

Astounding aimed slightly higher than many pulps, as it preferred stories with scientific flavour mixed with adventure. Even so, it remained far less “scientific” than Science Wonder, which featured detailed sections on technology and commentary from specialists. This story blends espionage elements with speculative science, creating a spy-like chase for a dangerous invention. The trauma of the First World War likely shaped the fascination with extreme technologies and the anxiety surrounding rapid scientific progress. This mixed attitude toward science appears here as well. The narrative presents science as morally neutral. It becomes dangerous only when handled by someone reckless. The same brilliance that creates the Osmotic Liberator also creates the Death Projector. Also, Keane’s intelligence increases his potential for harm, rather than making him ethical.

The Stolen Mind Narrative Structure and Themes

Staley uses third-person limited narration focused mainly on Quest. This approach sets up a challenge, since the plot requires the description of a disembodied mind. The story manages this through vivid images of confinement. Quest’s will is described as “compressed to the proportions of an atom” and linked to Keane through “conduits” and “tentacles.” These images turn an abstract idea into something physical and oppressive. The effect feels unsettling because it suggests a mind trapped inside its own awareness.

The Science of Consciousness Transfer

Staley mixes real chemistry concepts, such as osmotic pressure, ionisation, and electrolysis, with complete fantasy. According to the story, the Osmotic Liberator works on several ideas:

Different solutions carry different osmotic pressures

Consciousness behaves like an ionic solution

The human body acts as a “catalyser”

The mind can “flow” out and enter another host

Two minds connect when “will frequencies” match

This explanation sounds scientific enough to keep the plot moving, although it avoids specific detail. The focus stays on the experience rather than the mechanics. The idea of “will vibrations” echoes early twentieth-century enchantment with radio waves, which often inspired stories about invisible forces influencing the mind.

The Death Projector

The Death Projector uses “invisible light rays of a certain wave-length” combined with “short radio waves” and a “tellurium current-filter.” These elements produce a destructive field. Two operators can supposedly create a “circle of destruction a thousand miles in diameter” in ten minutes. This makes the weapon seem more dangerous than nuclear technology, which had not yet been imagined in 1930. The Death Projector works as a plot driver and a thematic warning about the “invention without responsibility”. The story barely explains its function beyond its destructive reach, which reinforces its role as a looming threat.

Author: M. L. Staley

M. L. Staley remains a mystery in early pulp science fiction. I imagine two possibilities: the author may have been an established writer using a pseudonym, or someone who produced one strong story and never returned to the genre. The quality of the narrative suggests experience. The technical references point to either scientific knowledge or solid research. There is something curious about Staley’s disappearance from the field. The author delivered a clever and creative story for a major launch issue, yet nothing else under that name seems to exist. It leaves open the question of whether more stories hide behind other bylines.

My Thoughts

I enjoy this story because it blends genres I like, especially espionage mixed with body-swap themes. The plot may feel familiar today, yet a reader in 1930 would not have seen it as predictable. The tale even contains a slight gothic touch, since Quest remains fully aware but unable to act. I value autonomy, so his situation disturbed me more than many horror stories. The image of his will “compressed to the proportions of an atom” while Keane’s dominates him “like foam” feels genuinely nightmarish.

Another part I enjoyed is the shift regarding who truly plays the villain. It is not exactly a twist, but it adds movement and makes the story more playful.

One detail you will notice here—and in many pulp stories from that period—is the use of foreign stereotypes. The “ambitious Balkan power” and Dr Nukharin reflect common pulp habits from the 1930s, as Eastern Europe often appeared as an undefined threat. The story also ends with an awful neat resolution, which was common at the time. The hero often receives recognition from some authority figure, which ties everything together quickly. Interestingly, there are no women in this story. That feels odd, yet also refreshing. A female character would likely have been written as an assistant, love interest, or damsel in distress—possibly all at once.

Conscious Transfer Theme

This story reminded me of others with similar themes, both modern and older. One example is Get Out. Jordan Peele’s film also uses forced consciousness transfer, creating horror through stolen bodily autonomy. The Coagula procedure mirrors the Osmotic Liberator, and Chris’s “Sunken Place” resembles Quest’s trapped state. Another example is Being John Malkovich (1999). Spike Jonze explores the idea of controlling someone else’s consciousness, including the chaos caused when several people occupy the same mind.

Wrapping Up

“The Stolen Mind” deserves attention as an early work dealing with consciousness transfer. Its appearance in Astounding’s debut issue helped shape the magazine’s blend of adventure and speculative thought. The story anticipates many later debates about mind, identity, and control. I genuinely enjoyed it. Whether we fear brainwashing, coercion, emotional manipulation, authoritarian pressure, or algorithmic influence, we understand the terror of losing control over our own actions.

If you’re keen to explore more classic stories or related analyses, feel free to browse the other posts listed below.

Other stories from Astounding Stories

More Works with mind transfer and body-swap fiction:

Being John Malkovich

The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde

Another vintage pulp magazine:

Science Wonder Stories, Vol. 1, No. 2

Original Astounding Stories issues at the Internet Archive.

Disclaimer: The story featured on this page is in the public domain. However, the original authorship, magazine credits, and any associated illustrations remain the property of their respective creators, illustrators and publishers. This material is provided for informational and educational purposes only and may not be used for commercial sale.